100% of people who drink eight glasses of water eventually die.

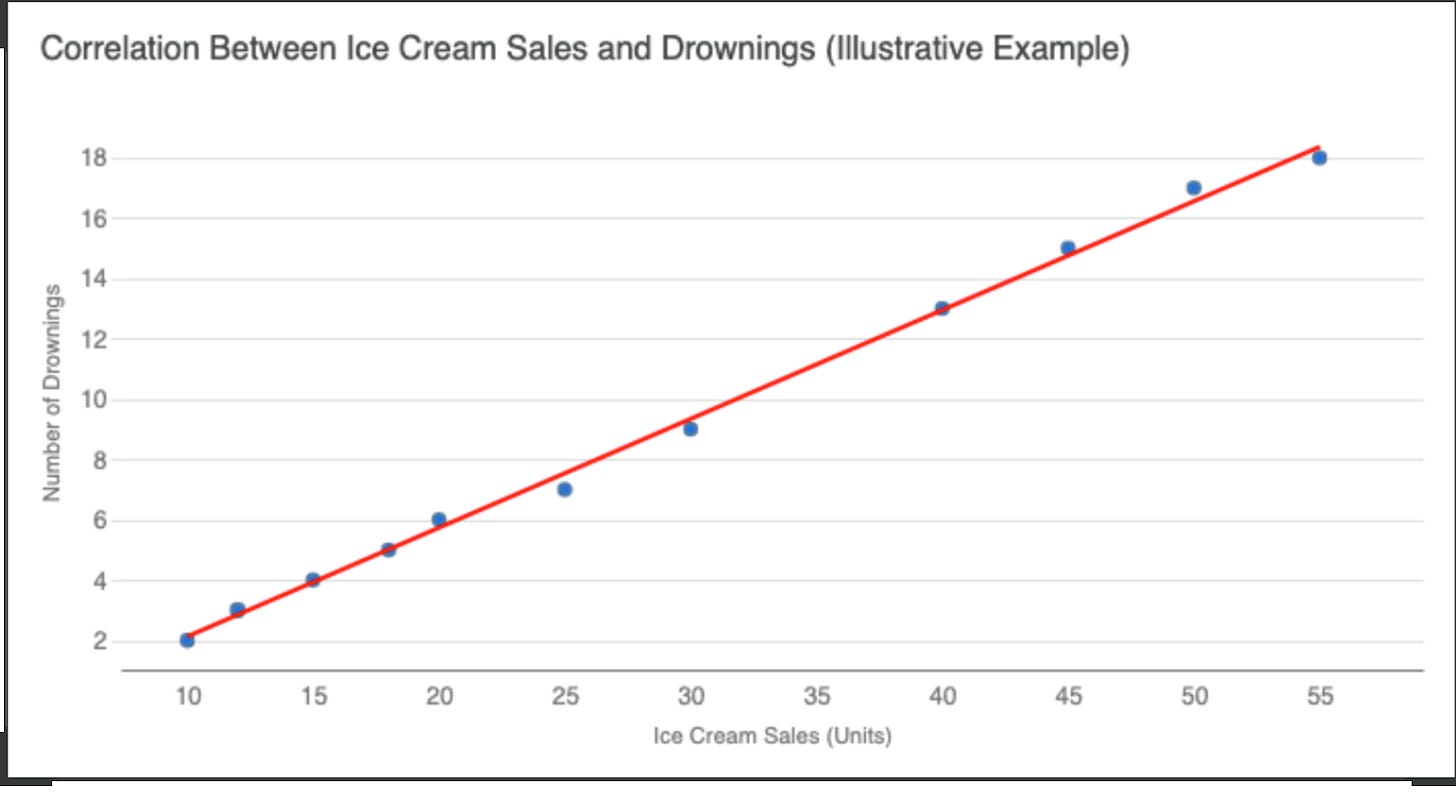

Countries with higher ice cream sales have higher drowning rates (both correlate with summer weather)

People who go to hospitals have higher mortality rates than those who stay home.

The science of epidemiology has achieved notable success in identifying the cause of specific diseases. The outbreak of cholera in 1854 in London was traced to a public water pump that dispensed copious doses of contaminated water. This outbreak in Soho killed 600 people in a few weeks. Dr. John Snow, who was skeptical of the ‘miasma’ theory of disease, carefully mapped all the cases. No one at a nearby brewery contracted cholera because they drank beer instead of the water from the Broad Street pump. This example highlights the importance of a single individual conducting a careful and thorough investigation to identify the cause of a disease. It is the poster child of great epidemiology.

Semmelweis applied basic epidemiological principles to demonstrate that his colleagues never washed their hands between examining women during or after childbirth, gaily transferring bacteria and slime from one woman to the next, resulting in puerperal fever and significant mortality. Not surprisingly, since medicine and doctors are pretty conservative and resistant to being swayed by facts, no one believed him. In fact, he was vilified by the medical establishment, a common occurrence when tradition triumphs over reason.

The identification of Typhoid Mary in New York in the early 1900s serves as another classic example of the benefits of careful and targeted epidemiological investigation. Mary Mallon was a cook for several families, most of whom suffered outbreaks of typhoid fever. She was identified as an asymptomatic carrier of this scourge by a sanitary engineer, George Soper, although she never accepted that she was the cause. Eventually, she was arrested and lived for over 20 years in isolation to keep the public safe.

There are a variety of more modern-day successes. The epidemic of AIDS in the gay community led to the rapid identification of HIV. The astounding speed with which the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 epidemic is perhaps the most recent highlight. On a micro scale, the identification of a sushi restaurant in Montana that sickened over thirty people and caused a couple of deaths, which had served raw or undercooked morel mushrooms, is notable. Moreover, we rely on good epidemiology to rapidly identify the farms or food processors that consistently contaminate our food with harmful bacteria, bits of metal or plastic, allergens, or a range of unwanted nasties. The most recent outbreak of measles in children in Texas was due to the avoidance of a safe and very effective vaccine. This one was a no-brainer, a result of systemic misinformation.

A common theme runs through most of these examples. Each one is intensely focused on finding a single, simple cause for a well-defined disease. It requires careful observation, boots on the ground, personal interviews, and then connecting all the dots. What they do not rely on is the blunt force of mindless statistics. Because that’s where, for me at least, epidemiology goes off the rails. When people attempt to use epidemiological data on a grand scale, such as to determine the one clue to longevity, it fails miserably. The same is true in trying to find the cause of various cancers, dementia, or heart disease.

No mathematical magic or statistical shenanigans can dissect the complexity of these issues. The use of multivariate analysis should be banned for our protection. Invariably, it leads to false leads and bad assumptions. Mining data from gigantic databases of questionable quality or meta-analysis may provide employment for some academics, but it produces precious little helpful information.

At times, it becomes absurd. Years ago, a wonderful article was published in the Journal of Irreproducible Results about the dangers of pickles. It pointed out that 99.9% of all people who died from cancer had eaten pickles. 97% of people involved in automobile accidents had eaten pickles in the previous month. 93.02% of juvenile delinquents come from homes where pickles are eaten. Even worse, all those born between 1920 and 1935 who ate pickles, if not dead, have wrinkled skin, no teeth, and brittle bones. This article brutally exposed medical and epidemiological humbug. It is widely quoted in any discussion to illustrate that correlation does not establish causation.

But can it be useful in reverse? In other words, can it debunk various causes that people like to claim? Let's use protein as an example. We are currently in a protein mania phase, with every health influencer claiming that you need to eat more protein (I wrote about this fake epidemic in a Substack article, ‘Protein Toxicosis’). Let’s examine some basic epidemiological data comparing the USA to a few other countries regarding protein consumption and longevity.

USA - 124 gms per person per day. Average life expectancy - 79.4 years

Greece - 65 gms per person per day, Average life expectancy - 83.1 years

China - 124 gms per person per day, Average life expectancy 77.6 years

Ridiculous takeaways:

If you eat half the amount of protein, your life expectancy increases by an astounding 4.66%.

Living in China will reduce your lifespan, despite all the protein, tai chi, and medicinal mushrooms that you eat.

While these conclusions are bunk, super-heroic daily doses of protein are obviously of little value, except to the influencers who peddle protein powders.

This is not the only example in which epidemiological data contradict many long-held beliefs. “Breakfast is the most important meal of the day” — except it isn't. In many cultures with better health and mortality statistics, breakfast is often an afterthought, and the first decent meal of the day occurs much later in the day. The Supplement Industrial Complex pushes Vitamin D as if it were magic. If one compares vitamin D supplementation rates vs. health outcomes across different latitudes, it turns out that Northern countries with lower sun exposure often have better health outcomes than sun-drenched regions, despite lower vitamin D levels.

In addition to these notable failures are the margarine vs. butter wars, where "heart-healthy" margarine was found to contain harmful trans fats. Hormone replacement therapy has flip-flopped as much as the average politician.

I remain embarrassed about a study that bears my name as one of the authors. I was the pathologist who reviewed all the cases of acute myeloid leukemia as part of an extensive cooperative study. My only task was to verify the diagnosis and classify the type of leukemia. The statisticians obtained this huge database, crunched the numbers, and found one association that they concluded was statistically significant. Without ever having the chance to review the manuscript—these were the days when anyone involved in a study had their name on the manuscript and before journals demanded that each author certify their approval of the research and confirm their significant role in the conclusions—it was titled “Maternal drug use and risk of childhood nonlymphoblastic leukemia among offspring. An epidemiologic investigation implicating marijuana (a report from the Children's Cancer Study Group).” Needless to say, there were many methodological shortcomings, and subsequent studies failed to confirm the association. Indeed, one larger study suggested the inverse—that marijuana decreased the risk of leukemia. So much for grand epidemiological studies.

One of the clearest and amusing takedowns of correlation and causation was written by Fitzpatrick in the Tyranny of Health,

“The Japanese eat very little fat and suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or Americans.

The French eat a lot of fat and also have fewer heart attacks than the British or Americans.

The Japanese drink very little red wine and suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or Americans.

The Italians drink excessive amounts of red wine and also suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or Americans.

Conclusion: Eat and drink what you like. What kills you is speaking English.”

— Michael Fitzpatrick, The Tyranny of Health, 2000, quoted in Wilson Quarterly

A striking feature of most successful epidemiological investigations is that they were conducted by a single individual or a small group. This is why it is essential to have a well-funded, robust public health system with expertly trained and determined investigators. Epidemiology works brilliantly for identifying causes of specific diseases, but becomes misleading when applied to complex, multifactorial health outcomes. However, it can be used to challenge conventional beliefs by illuminating the lack of correlation in other cultures and countries. It can expose much of the nutritional nonsense with which we are deluged.

I suspected the danger of speaking English

Thanks , Denis

Your thoughts are always welcome

Milton

Post hoc ergo propter hoc